THE BOARD’S ROLE IN CEO SELECTION

Historically, incumbent CEOs anointed their successors, but that all changed in the post Sarbanes-Oxley environment that required the consideration of the entire board. Now the CEO’s job involves preparing one or two strong internal candidates—ensuring leadership continuity and the CEO’s legacy. However, selecting the right person from among internal and external candidates remains the single most critical task the board has. Therefore, the job of directors is to develop a disciplined and thorough succession plan, execute it, and finally choose the best candidate. This requires a systematic three-step process that readies the candidate for transition to the executive chair.

Step One: Revisit the Strategic Principle

Step One: Revisit the Strategic Principle

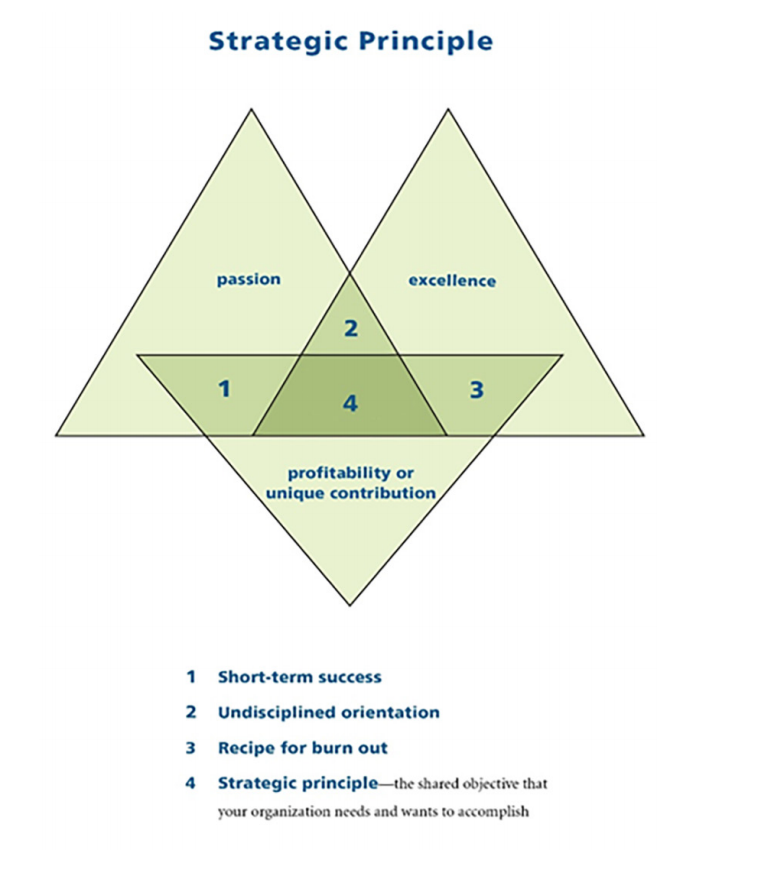

Success depends on a strong strategic principle—a shared objective about what the organization wants to accomplish. The strategic principle guides the company’s allocation of scarce resources—money, time, and talent—and revisiting it when a new CEO needs to take over helps to ensure a profitable future.

Directors of successful boards assume the roles of the architect, steward, and guardian of the strategic principle. This job cannot be outsourced, completed, or scheduled, and it’s the most uncertain thing directors do because it involves speculation about unknowns and requires a journey into murky waters.

The strategic principle doesn’t merely aggregate a collection of objectives. Rather, this simple statement captures the thinking required to build a sustainable competitive advantage that forces trade-offs among competing resources, tests the soundness of particular initiatives, and sets clear boundaries within which decision-makers must operate. When companies face change or turmoil—and CEO selection brings both—the 2 and unexpectedly, and they have ensured the organization is sufficiently talent-laden to allow for a seamless succession. These kinds of boards are as stellar as they are rare. Setting the criteria for the new CEO starts with decisions about what the success factors for the new CEO will be. These decisions often begin with an evaluation of the incumbent CEO, but they can’t stop there. The board’s tendency will be to try to select a clone of the existing CEO, even though the strategic direction of the company promises to vary drastically from the current one. Directors should develop a clear view of what will make the new CEO successful and express their expectations about financial targets, the complexity of the changing organization, the scope of the CEO’s role, and general market or industry conditions. If no agreement about the abilities and vision of the next CEO exists, agreeing on a candidate will prove impossible. When directors develop a shared perspective about the future business environment and the strategic challenges the company and the new CEO will face, however, they take the first critical step toward a successful transfer of power. The next step is to define the capabilities the new CEO will need and the specific qualities, skills, and behaviors the person should demonstrate. When I work with boards on CEO selection, I start with general questions that include the following: • What type of person will “fit” the needs of the future company? • Should the new person fit the existing culture? • Or, should a new leader use a turnaround style to overcome obstacles the culture has created? • What values should the new CEO evidence? I ask board members to start the selection process by finding candidates that I call “multibusiness leaders.” At a large company, these people typically run a market within the company or a smaller company that reports to the parent. Sometimes these candidates have led smaller strategic principle acts as a beacon that keeps the ships from running aground. Even when the leadership changes, or the economic landscape shifts, the strategic principle remains the same.

The strategic principle doesn’t merely aggregate a collection of objectives. Rather, this simple statement captures the thinking required to build a sustainable competitive advantage that forces trade-offs among competing resources, tests the soundness of particular initiatives, and sets clear boundaries within which decision-makers must operate. When companies face change or turmoil—and CEO selection brings both—the 2 and unexpectedly, and they have ensured the organization is sufficiently talent-laden to allow for a seamless succession. These kinds of boards are as stellar as they are rare. Setting the criteria for the new CEO starts with decisions about what the success factors for the new CEO will be. These decisions often begin with an evaluation of the incumbent CEO, but they can’t stop there. The board’s tendency will be to try to select a clone of the existing CEO, even though the strategic direction of the company promises to vary drastically from the current one. Directors should develop a clear view of what will make the new CEO successful and express their expectations about financial targets, the complexity of the changing organization, the scope of the CEO’s role, and general market or industry conditions. If no agreement about the abilities and vision of the next CEO exists, agreeing on a candidate will prove impossible. When directors develop a shared perspective about the future business environment and the strategic challenges the company and the new CEO will face, however, they take the first critical step toward a successful transfer of power. The next step is to define the capabilities the new CEO will need and the specific qualities, skills, and behaviors the person should demonstrate. When I work with boards on CEO selection, I start with general questions that include the following: • What type of person will “fit” the needs of the future company? • Should the new person fit the existing culture? • Or, should a new leader use a turnaround style to overcome obstacles the culture has created? • What values should the new CEO evidence? I ask board members to start the selection process by finding candidates that I call “multibusiness leaders.” At a large company, these people typically run a market within the company or a smaller company that reports to the parent. Sometimes these candidates have led smaller strategic principle acts as a beacon that keeps the ships from running aground. Even when the leadership changes, or the economic landscape shifts, the strategic principle remains the same.

Assuming the board started CEO succession 3-5 years before the incumbent’s departure, directors have already committed to identifying and developing internal candidates. They have given these candidates exposure to the board, key clients, and stakeholders. Similarly, the board has at least a rudimentary plan for transitioning leadership. As history has shown, the best succession plans start with a clear vision of the future and a strong strategic principle for getting there.

Sometimes directors don’t have the luxury of developing and monitoring a succession plan and then creating a timeline for transition, however. Too often, a crisis shortens the timeline and forces the board into an even higher-stakes situation with the cost of picking the wrong CEO even more ominous.

The transition from one CEO to the next is a risky endeavor fraught with opportunities to lose top talent, stakeholders, and key customers. When the board takes its eyes off the strategy, these risk factors become more threatening. Ideally, directors have consistently and conscientiously monitored the company’s strategy to determine how to align their objectives with the company’s current leadership capabilities to set the stage for the future leader.

Step Two: Set Criteria for Selecting the New CEO

Directors who have focused on CEO competencies through systematic evaluations start the selection process ahead of the game. These boards have regularly considered potential replacements, should the incumbent CEO leave suddenly and unexpectedly, and they have ensured the organization is sufficiently talent-laden to allow for a seamless succession. These kinds of boards are as stellar as they are rare.

Setting the criteria for the new CEO starts with decisions about what the success factors for the new CEO will be. These decisions often begin with an evaluation of the incumbent CEO, but they can’t stop there. The board’s tendency will be to try to select a clone of the existing CEO, even though the strategic direction of the company promises to vary drastically from the current one.

Directors should develop a clear view of what will make the new CEO successful and express their expectations about financial targets, the complexity of the changing organization, the scope of the CEO’s role, and general market or industry conditions. If no agreement about the abilities and vision of the next CEO exists, agreeing on a candidate will prove impossible.

When directors develop a shared perspective about the future business environment and the strategic challenges the company and the new CEO will face, however, they take the first critical step toward a successful transfer of power. The next step is to define the capabilities the new CEO will need and the specific qualities, skills, and behaviors the person should demonstrate. When I work with boards on CEO selection, I start with general questions that include the following:

• What type of person will “fit” the needs of the future company?

• Should the new person fit the existing culture?

• Or, should a new leader use a turnaround style to overcome obstacles the culture has created?

• What values should the new CEO evidence?

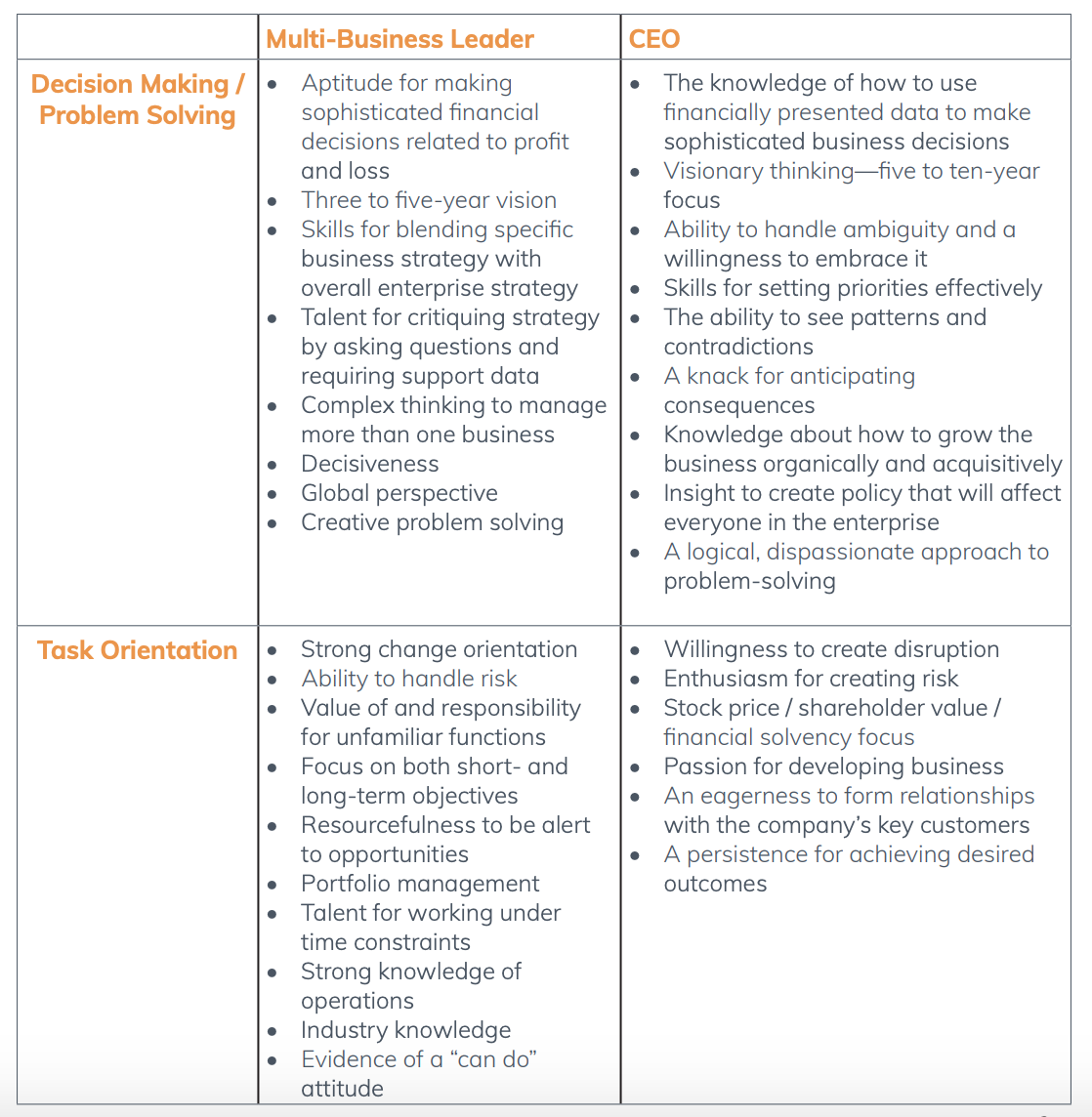

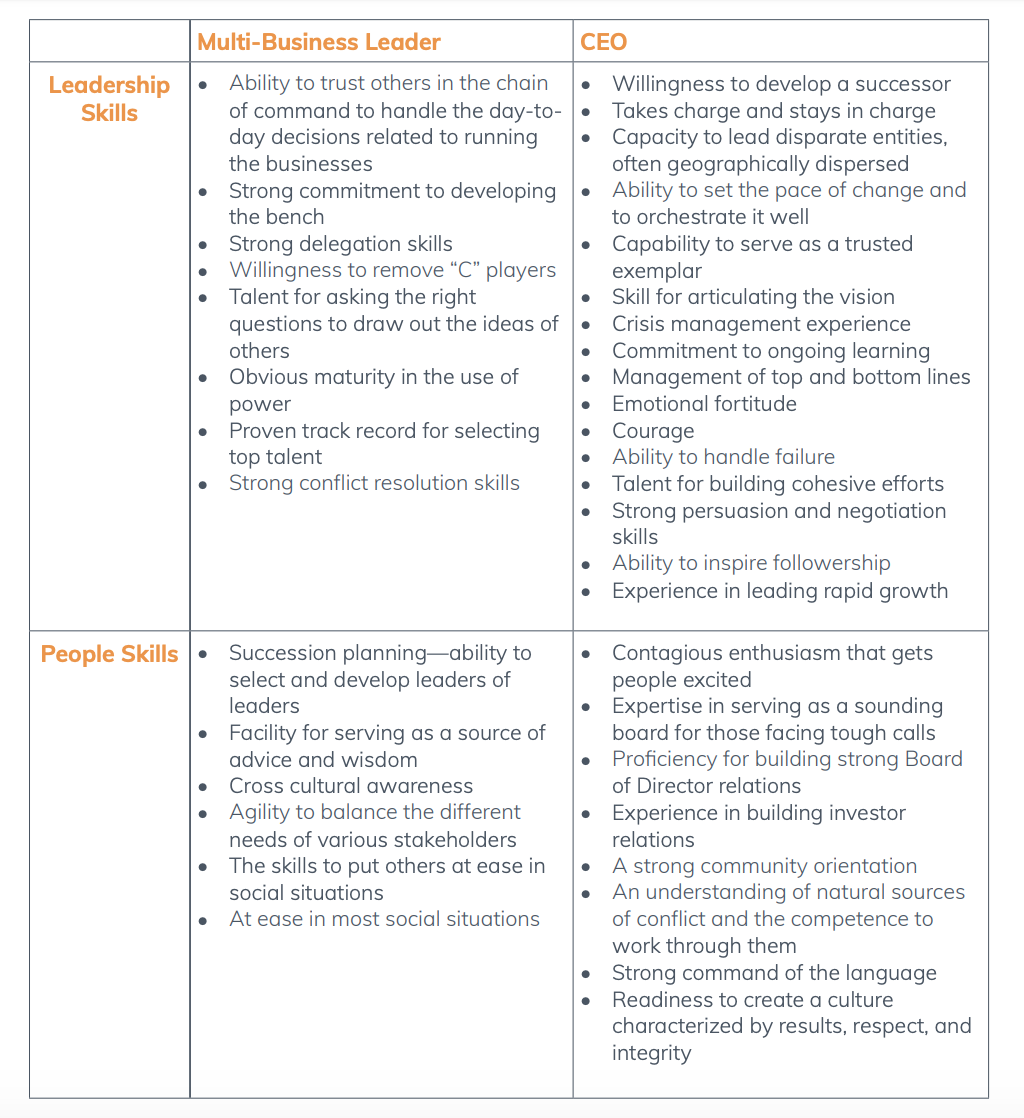

I ask board members to start the selection process by finding candidates that I call “multi-business leaders.” At a large company, these people typically run a market within the company or a smaller company that reports to the parent. Sometimes these candidates have led smaller companies and are ready to step up. At other times, the candidates are people who have managed other managers. In all cases, taking on the CEO’s role should represent a significant step up—not a huge leap. Candidates should evidence all the multi-business success indicators and demonstrate a willingness and ability to move to CEO-level performance. This is how I think about how a multi-business leader transitions to the CEO chair:

Once the search committee has set and prioritized the criteria for selection, it is ready to develop the roadmap for a successful transition.

Step Three: Develop the Process for Selection

The CEO selection process should be a systematic, thorough process that gives the board impartial, indispensable data they will need to make selection decisions. Done well, this process will protect the financial aspects of the business, prevent the departure of key talent, avoid costly hiring mistakes (usually four times the CEO’s base salary), build confidence among all stakeholders that you have selected the best person to run the company, and engender legally defensible hiring decisions—thereby reducing risk. I use the following nine-step approach:

1. Create a profile of the leadership attributes and behaviors needed to successfully fulfill the role and responsibilities.

2. Review the profile with the entire Board of Directors and refine as needed.

3. Conduct individual discussions with each board member regarding the organization, strengths, challenges (internal as well as market-driven), and leadership needs in the future.

4. Explore recruitment options for finding this person if no internal candidates appear to be ready.

5. Set the ideal timeline for hiring and transitioning leadership.

6. Evaluate all internal candidates by doing the following:

- Assess performance in their business units.

- Review personal performance for the past three years.

- Interview each candidate.

- Conduct 360 degree interviews of their peers, direct reports, and board members.

- Administer assessments to internal candidates to determine decision making skills, learning ability, financial acumen, critical thinking, business-related personality traits, and leadership style.

7. Debrief each internal candidate’s data, pointing out how to leverage their strengths and mitigate their limitations, thereby improving performance in the short run.

8. Debrief all findings with the search committee to make recommendations about developmental needs for candidates and likelihood that each will be successful in the CEO role.

9. Review the process and candidate evaluations with the full board, recommend one of the candidates for promotion, or when necessary, suggest opening the search to external candidates.

Plan the Transition

I cannot overstate the value of choosing an internal candidate. When this happens, there’s very little that needs to change about pre-boarding, exposure to the board, structured time with the current CEO, and getting to know the executive team. When the board has chosen an internal candidate, therefore, directors should concentrate on developing and implementing a communication strategy for the entire organization and a timeline for the transfer of leadership. A major concern should be retaining the other candidates who did not receive the promotion. The chairman of the board and the incumbent CEO should have private conversations with each candidate before telling anyone else inside or outside the company what the decision has been.

When directors cannot promote from within, they need a different approach. First, they should tell any internal candidates before opening the search. Some people may be disappointed, but if the company’s leaders treat them with respect, they are much more likely to remain in place. If they feel blindsided or deceived, you can bank on one of two things: the loss of a top performer or a decline in performance from that candidate. Effectively managing the transition brings other benefits too.

• People experience fewer distractions.

• Customers don’t feel the change. • Revenue remains steady.

• The risk of losing talented people abates. • Repute in the industry increases.

• Morale improves.

Conclusion

Companies experience vulnerability during any major change in leadership, but a well defined approach to CEO selection significantly mitigates those risks. However, all the effort is only worthwhile if the board makes the right decision. Interviews, resumés, and references won’t give directors all the vital information they’ll need to make one of the most critical decisions that they simply can’t get wrong. They need more than subjective opinions that can be both biased and wrong. Instead, they require objective data and reliable data to help them choose the person who will have the most power in the organization.

© 2020 The Board Mindset. All rights reserved. Permission granted to excerpt or reprint with attribution.

Helping organizations and individuals achieve a more powerful success mindset.

Contact us to experience the dramatic growth and improvement.

Schedule a Call